Closing the Gap Between Citizen Science and Academic Research

What’s the biggest difference between “citizen science” and academic research conducted by scientists? Whose job should it be to digitalize colossal historical data, such as the historical documents often discovered in old families’ estates? And how much responsibility should academia take on in applying research to the real world? We visited two researchers in Kanazawa who are spearheading unique initiatives to promote citizen science.

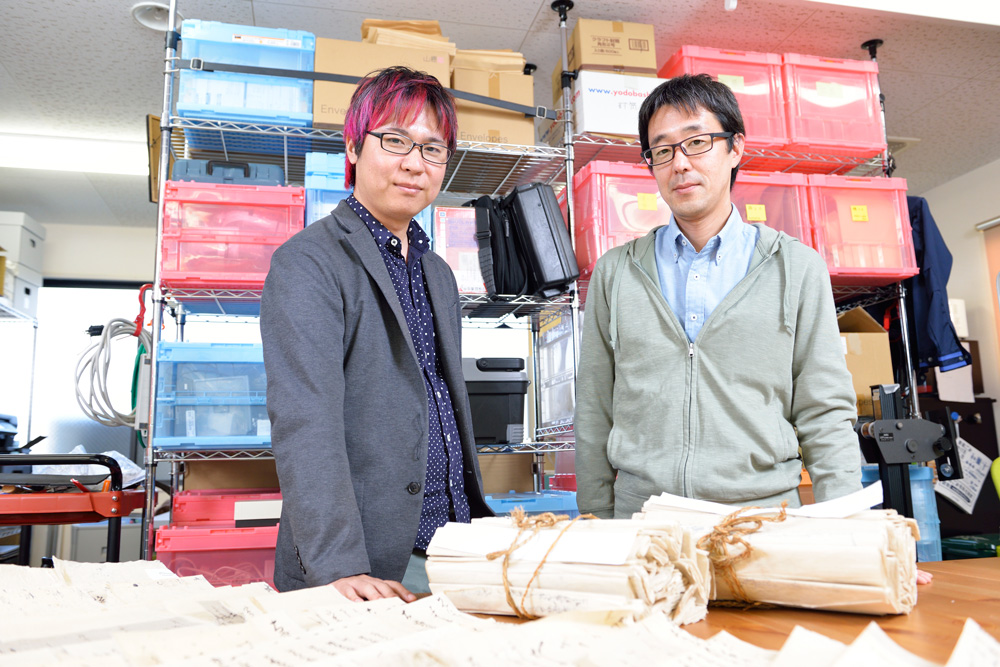

Ask an Expert: Hiroshi Horii, Founder, AMANE LLC.

Dr. Hiroshi Horii is an IT system expert and the founder of AMANE, a research company that gathers and analyzes paleographical and ethnographical scholarly materials to create new value for the historical data. The company has a staff of highly accomplished experts in a range of research fields. Dr. Horii earned his doctorate degree in information science from Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology in 2002. He works as an adjunct professor at Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology. Dr. Horii’s wife, Dr. Misato Horii, an early modern Japanese history expert, serves as an executive officer of AMANE.

Ask an Expert: Tsubasa Yumura, Researcher, ICT Testbed Research and Development Center, National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT)

Dr. Yumura specializes in ubiquitous computing and human-computer interactions. He joined NICT in 2015 after working for a leading electronics manufacturer and a location information business. Dr. Yumura also serves as a researcher for Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology’s IoT Social Infrastructure Hub project. His experience includes leading/operating such projects and events as NASA International Space Apps Challenge, NicoNico Gakkai Beta, Ouchi Hack Club and NT Sapporo.

Serving as universities’ expert resource to fulfill local needs

As more researchers around the world are practicing digital humanities – a crossroad where humanities meet information technology – the need for converting historic documents and artifacts into digital data also continues to grow. Transforming humans’ handwork into machine-readable data is a laborious process, and there are never enough helping hands to be found.

As a solution to the problem, Dr. Hiroshi Horii launched AMANE, the Kanazawa-based research business, in 2009. AMANE contracts with academic institutions and municipal governments to unearth and analyze historical documents and artifacts in their areas and to convert them into digital data.

“Our job is to create data, but we aren’t here just to do the behind-the-scenes work. We are the country’s smallest research organization designated as a recipient of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)’s Grants for Scientific Research,” Dr. Horii said. “Finding ways to create value-added data is a research subject in itself. This is where our ingenuity shows.”

The company has many in-house scholars with expertise knowledge on history and antique documents.

“Envisioning researchers’ career paths outside of the university setting is one of our objectives,” Dr. Horii said.

He pointed out that universities these days don’t have adequate “manpower” to carry out research projects.

“There’s a growing manpower shortage. It’s more serious than when I was studying information science in a graduate program, and I believe this trend will continue for the foreseeable future,” he said. He noted that professors used to have their students volunteer for some fieldwork, but that’s also becoming a thing of the past as well, because that can create legal complications.

“Research, education and social contribution are the three legs of the university stool. In reality, though, universities are mostly judged on their research work, particularly on peer-reviewed research papers. Researchers could use a lot of support to produce quality papers. If we can assemble a team of researchers who have the right expertise to support a research project, they can divide responsibilities to efficiently carry out the project. And we want to show how people can make a career out of providing their expertise that way.”

In addition to carving out a new profession in the research world, Dr. Horii said he had another motivation in launching his business: Crossing the “Death Valley.”

“University researchers often run into big obstacles in carrying out a real-world application of the basic technologies they developed. And that blockage is called the Death Valley,” Dr. Horii said. “University researchers have lots of restrictions. They cannot do anything that might cause harm to society, though the local communities want researchers to follow through with the real-world application of their research,” he said. “Once you reach the edge of the valley, you get the urge to cross it to the other side. That desire prompted me to start this business.”

‘Let’s use that technology more creatively!’

While Dr. Horii strives to create academic research positions in the private sector, his fellow Kanazawa-based scientist, Dr. Tsubasa Yumura, has made it a point to stay in both the academic and non-academic worlds simultaneously as a way to pursue his research goals.

For example, he has helped host the International Space App Challenge in Japan for the past eight years. The Challenge is an annual global hackathon organized by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), in which participants develop apps that use satellite data to help solve the world’s problems. For the 2016 hackathon, Dr. Yumura, as a participant, developed an image-typing projection keyboard – a virtual keyboard projected onto a surface, from which projected images of letters jump out and float through the air as you type.

“It was just for fun,” Dr. Yumura said of the keyboard, which became the talk of the town. “But many university professors were intrigued by it, prompting some of them to write research papers on it.”

Dr. Yumura, who works as a researcher at the National Institute of Information and Communications and Technology (NICT), also leads an online community called ‘Ouchi (home) Hack Club,’ where people exchange information about apps that make your life easier. These apps include one that reminds you about trash day by turning your front door’s light a different color. Another app lets you know it’s time to shut your bathtub’s faucet when the tub has enough warm water in it for bathing.

Dr. Yumura said he wonders whether these projects that does “on the side” of his day job can be legitimately called “research.” Nonetheless, he believes there are many ways for citizens to pursue science.

“Currently, ‘citizen science’ is mostly driven by academia. But citizens could drive it by simply creating devices or systems that they want,” Dr. Yumura said. “As democratization of technologies advances, sensors, projectors and many other parts and devices are becoming more affordable. Social media also serves as an alternative to research paper writing, enabling researchers to disseminate information more cost-effectively,” Dr. Yumura said. “Citizen science used to mostly involve amateur astronomers and insect researchers. But those interested in information technology and engineering can all be part of citizen science now.”

Saddling over the boundary between the academia and citizens

So, what should the research world of the future look like? How should projects be carried out?

Science Report was there as Drs. Horii and Yumura sat down to discuss it recently.

Dr. Horii: “I think Dr. Yumura and I share something in common, in that we are both trying to figure out how citizens can contribute to research involving local historical materials, and where we, as academia, fit into citizen science. I’ve transitioned into the private sector, while Dr. Yumura is an academic researcher. And that leads to the bigger question of how to define ‘university research.’”

Dr. Yumura: “That’s the question that’s been tormenting me.” (laugh)

Dr. Horii: “To work as a team, we first need to set a goal and divide our responsibilities in the most efficient manner possible. The problem is that it’s not clear what the goal of academic research is supposed to be – right?”

Dr. Yumura: “I think the way we do science should change with time. But the system hasn’t changed since the pre-internet era. For example, the system of peer review – which requires anonymous exchanges of feedback – is designed for communication via snail mail. As a result, we aren’t taking advantage of modern communication methods like email and online chat functions for peer review. People may fear that we are throwing the baby out with the bathwater by restructuring the long-standing system. But most researchers also realize that we cannot keep doing the same thing. Recently, the way we publish research papers began to change a little bit. It’s now considered a standard practice to post papers on arXiv, an open-access repository of electronic reprints that is operated by Cornell University.

Dr. Horii: “I think the evaluation matrix can be made more diverse. I would also welcome more active discussions on comments provided in peer review. For example, if your work receives a lot of positive feedback, that represents the value shared by people providing the feedback. This is another reason why I believe in open science.”

Dr. Yumura: “The programmers’ community can be a model for open science. The website where people can post source codes for open access is designed in such a way that you can see which open software are most helpful. So, in a way, that’s serving as a software review system. There are also many, many different workshops and events being offered for programmers in Tokyo every day, which provide opportunities for them to demonstrate their work and mingle. I sometimes wonder if members of academia used to interact this way. If that’s the case, we could perhaps bring back that part of the academic world of the past.”

Interviewer: Rue Ikeya

Photographs: Toshiyuki Kono (article); Yuji Iijima (column)

Released on: Dec. 10, 2020 (The Japanese version released on Dec. 10, 2019)

Providing Open Access to Academic Research Papers and Research Data

Amid the open science movement, there is increasing interest in gaining open access to research papers and data that belong to research institutions. In response to the growing demand for open access in institutions, the NII has developed JAIRO Cloud, a cloud-based institutional repository service. An institutional repository is an archiving system that research organizations develop in order to collect, preserve and disseminate digital copies of their research outputs. As of the end of 2018, 558 institutions used the repository service.

JAIRO Cloud is made possible by the WEKO3, a repository software. The Research Center for Open Science and Data Platform (RCOS) develops and operates three separate systems for three different purposes: one system for data management; another for data publication; and the third for data discovery. WEKO3 is the system for data publication. With the goal of maximizing research data dissemination, WEKO3 is equipped with a flexible metadata and workflow management functions.

“One of the things we paid particularly close attention to in developing the software was the flexibility of metadata management,” said Dr. Masaharu Hayashi, Project Assistant Professor at the ROCS.

Metadata is the data about data; it makes data search possible and easier. For example, the titles and dates of research papers, as well as the authors’ names, can be converted to metadata. In order to truly promote the dissemination of research and journal data, however, metadata needs to provide far more detailed descriptions, Prof. Hayashi said.

JAIRO Cloud is expected to launch in 2021. “We are hopeful that encouraging the dissemination of research data will lead to more thriving open science activities,” Prof. Hayashi said.