Team Japan Looks to Connect All the Climate Dots in the Arctic

For many Japanese scientists, the “end of the earth” is becoming a familiar corner of the earth.

Recognizing the urgent need to tackle climate change, Japan named its first-ever Arctic ambassador in 2013, followed by the Arctic Council’s admittance of Japan as one of its observer states. By late 2015, the country would develop “Japan’s Arctic Policy,” spelling out its commitment to Arctic monitoring and research as well as collaborations with the international research community. With hundreds of Japanese scientists working together under the framework of the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability (ArCS) – Japan’s national flagship project for Arctic research – the Arctic no longer seems like a faraway place on the end of the earth. It’s simply their research base.

Now, global leaders are hoping these Japanese scientists will help the world make sense of climatic changes in the Arctic with their data and analysis and address society’s needs. So, how is Team Japan trying to do just that? An expert from the National Institute of Polar Research answers to the question.

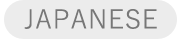

Ask an Expert: Hiroyuki Enomoto (The National Institute of Polar Research – NIPR)

Dr. Enomoto serves as professor at the NIPR and the director of the NIPR’s Arctic Environment Research Center (AERC). He holds an undergraduate degree from Hokkaido University and received his PhD in physical geography from Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich for his study on sea ice and climate. Prof. Enomoto has participated in various sea ice, glacier and cryosphere observatory programs in the Arctic and Antarctic and joined the NIPR in 2011 following his tenure at Kitami Institute of Technology in Kitami, Hokkaido. As vice project director of the ArCS, which was launched in 2015, Prof. Enomoto oversees the maintenance of global research and observation sites in the Arctic and assembles a delegate of experts to the Arctic Council to promote Japan’s “sci-tech diplomacy” efforts. Click here for his bio.

Japan’s Role as Expert Witness for Arctic Climate Change

Scientists are a hot commodity in global political scenes these days. Every stakeholder participating in such events as the Arctic Council’s meetings wants scientists by their side while making their points.

“Arctic climate change has global consequences, and people want to know why they are experiencing extreme climatic phenomena and what it means for the future. If you have ample, concrete scientific data to back up your policy proposal, more people will listen to you,” Prof. Enomoto says.

That’s where Japanese scientists come into the picture.

“People want scientists to find ways to use their research results in meaningful manners for the benefit of the society. I believe that’s the mission of the 21st Century Arctic research,” Prof. Enomoto says.

Prof. Enomoto points out, however, that the Arctic climate is changing so fast that the problems that the scientists are trying to tackle can be moving targets.

“Nature is moving fast, and it’s like humans are trying to catch up with it. But, nature continues to beat us to it,” Prof. Enomoto says.

This may mean that we, as an international research community, need to decide what is the most important thing to monitor, and develop “observation strategies.”

The Arctic Challenge for Sustainability (ArCS) aims to decode Arctic climate change by bringing together all the experts and resources that Japan has to offer on the topic just as its predecessor, the Green Network of Excellence (GRENE) Arctic project, did. (See Science Report 001) This “Team Japan” approach is drawing the attention of the global research community, according to Prof. Enomoto, who serves as part of the ArCS core leadership.

“People look at us as this compact team from a mid-latitude country going all out to advance the Arctic research,” Prof. Enomoto says. “Just because you are an Arctic country, that doesn’t necessarily mean you have the best know-hows for observing the region’s climate. Strategic selections of monitoring sites for long-term observations, climate forecasting and sea route planning through simulations, development of data archiving systems, providing information to the local community and fostering the next generations of scientists in the field – these are all areas where the Arctic countries could use fresh eyes to do better, and for Team Japan, being an outsider helps,” Prof. Enomoto says.

The Team Japan’s goals include setting new, higher standards for data gathering.

“We seek collaborations from the U.S. and Canada for simultaneous data-gatherings. We propose new observation methods to improve upon forecasting accuracy. All of this enables us to collect more and better data,” Prof. Enomoto says.

Among all parts of the Arctic, Greenland is seeing the fastest climate change, according to Prof. Enomono. Greenland is the world’s largest island with 80 percent of the area covered with ice sheet. In other words, Greenland comprises one of the two ice sheets that exist on earth with the other one being Antarctica. The ice thickness ranges from 1,500 meters near the shorelines to 3,000 meters inland. Ice slowly moves from its center to the shore and becomes an iceberg when it falls into the sea. (See Science Report 003)

“Greenland is a forerunner of climate change. Changes occurring there gives us an idea of what may also happen in Antarctica down the road,” Prof. Enomoto says. “On the ground, compressed layers of snow become an ice sheet. Lakes that dot the Scandinavian region and Canada are the remnants of an ice sheet from the glacial period that melted. The weight of the ice pushed up the ground to form hills. Greenland’s ice sheet is melting fast right now, which could eventually yield a series of lakes when the ice is all gone. At the COP 21, the Conference of the Parties that took place in Paris in 2015, participating countries set the goal of limiting the global temperature increase to a minimum of 1.5 degrees Celsius and a maximum of 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industry levels. Some predict an increase above 1.5 degrees could cause Greenland to melt away rapidly.”

Field observation on the Bowdoin Glacier in July 2016. The site is 20 kilometers from Qaanaaq, and the glacier is changing rapidly especially on its outer edges. Team Japan has gathered data here since 2013. Photo: Evgeny Podolskiy(From ArCS News)

Engagement with the local community is essential to the successful operation of research and observation projects. (See Science Report 005)

“We want local people to understand why we are here, and join us in data-gathering. We want them to help us with their local knowledge and experience and show us how to get around. We would share our data and analysis to help improve the quality of the locals’ lives. This is a challenge to communicate and build the relationship . We don’t want to come across as foreigners from a faraway country who invaded a population’s space and set up strange-looking measuring apparatus everywhere,” Prof. Enomoto says. “As a first step, we have been hold a series of workshops open to the local residents,” he says.

Team Japan has introduced the Arctic Data archive System (ADS), which brings together all the monitoring data, to the locals at one such workshops and was surprised by the hugely positive response of the participating residents.

“The conversation we had with the residents made us realize that we should include more social science data in addition to science data,” Prof. Enomoto says.

Prof. Enomoto says Team Japan is striving to provide a wider array of information to foster connections among the ecosystem, industry, global politics and regional security.

Interviewer: Rue Ikeya

Photographs: Yuji Iijima unless noted otherwise

Released on: Sept. 11, 2017 (The Japanese version released on April 10, 2017)