Getting Ahead of Climate Change

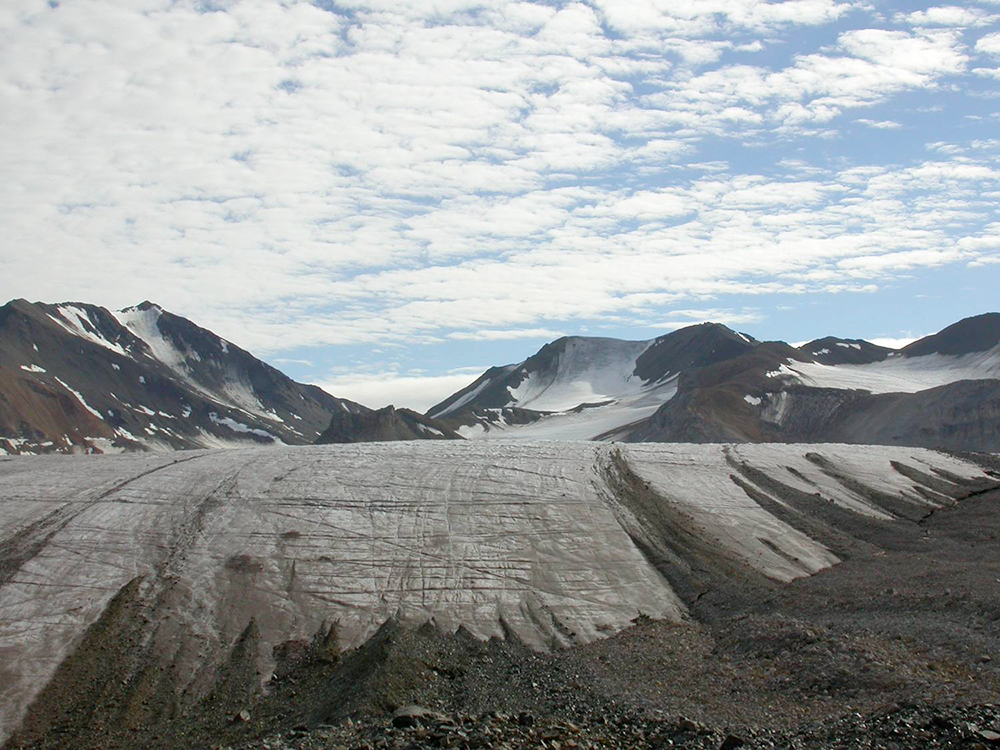

The Arctic is becoming dirtier — or, so it may seem to people who visit Greenland to find mysterious black speckles covering ice sheet, turning the entire landscape gray.

The soot-like substance is a microbe called Cryoconite, which has spread rapidly across ice sheet cover in recent years. The emergence of Cryoconite is an example of various ecological phenomena happening in the Arctic – the place where scientists say global climate change manifests in the most extreme forms before anywhere else in the world.

"That's what we call Arctic amplification," said Takashi Yamanouchi, professor emeritus at the National Institute of Polar Research who has led Japan's major Arctic research initiative, Green Network of Excellence (GRENE) Arctic Climate Change Research Project, since its inception in 2011 through 2016.

"The effects of global warming are far more visible in the Arctic than in any other place on the planet. In fact, the average Arctic temperatures have risen twice as fast as the global average," Yamanouchi said, explaining the importance of the research initiative. And the GRENE-Arctic is now giving people a glimpse into the future, including potential uses of the Arctic Ocean in ways we've never dreamed of before.

The GRENE-Arctic is Japan's ultimate attempt at decoding climate change mechanisms. It brings together 360 scientists from 40 research institutions — including the National Institute of Polar research and the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology — for cross-disciplinary investigations into all aspects of the Arctic climate system from the atmosphere to cryosphere.

The Arctic region refers to the area north of 66° 33' N latitude, and the Antarctic region south of 66° 33' S latitude. During the International Geophysical Year (1957-1958), there was much discussion and reporting about unusual ecological changes taking place in those regions ahead of the rest of the world. This brought polar amplification to scientists’ attention.

Recognizing the importance of the Arctic and Antarctic regions as the harbingers of global climate change, Japan soon launched observation programs in both the Arctic and the Antarctic. In 2011, Japan established the GRENE Arctic Climate Change Research Program, calling on the country’s best talents in the science community to join in the effort to understand the process of climate change and help combat its impact on human lives.

The Cycle That Will Never End

Unlike the Antarctic that sits on land, the Arctic is mostly comprised of ocean with sea ice floating over it. This explains why the Arctic experiences the effects of global climate change faster and more severely than the south, according to Prof. Yamanouchi, who has served as the GRENE-Arctic program’s project manager.

“Sea ice bounces off most of the sunlight that hits its surface, but as the ice thins out, the water underneath it absorbs more light, further accelerating the warming of the water. This so-called ice-albedo feedback is the chief cause of Arctic amplification,” Yamanouchi said.

Ice sheet over the land areas of the Arctic continue to melt at a startling speed, as well, impacting the wildlife and lives of the local residents.

The visible scars from the Arctic warming include the explosion of Cryoconite, the black spats found all over the surface of ice sheet in Greenland. But, Cryoconite doesn’t just create an unsightly vista. The GRENE-Arctic team has observed the ice under Cryoconite melts more as it receives heat from the light-absorbing black microbe.

“We now know such changes to the ecosystem further speed up the melting of ice and snow,” Yamanouchi said.

Ask an Expert: Takashi Yamanouchi, professor emeritus at the National Institute of Polar Research

Takashi Yamanouchi, professor emeritus at the National Institute of Polar Research, specializes in atmospheric science and polar climatology. He serves as editor-in-chief of Polar Science, an international quarterly journal. To view his bio, click here. For the Summary of Outcomes, GRENE Arctic Climate Change Research Project, click here.

Taking Advantage of Global Warming

In the meantime, the receding Arctic sea ice may be welcome news for those in the business of international trade.

“It opens up new possibilities for ocean shipping,” Yamanouchi said. “In our estimate, you can drastically shorten the travel distance between Japan and Europe by going through the Arctic Ocean instead of the Suez Canal,” Yamanouchi said. “But, in order to use the route for commercial purposes, you would also have to know how much safety and financial risks there are with bypassing the Arctic Ocean. People in the industry expect scientists to figure out how to compute all that.”

The GRENE Arctic successfully predicted the Arctic sea ice distribution for the summer of 2015 with little margin of error, and used the experience to draft a methodology for selecting the best ocean cargo routes. Russia, which owns oil fields in the Arctic, as well as China, Korea and other countries that have financial stakes in the region are reportedly interested in using this type of methodology to identify new and better routes.

The Heroes Who Came Before Us

Moving cargoes through the Arctic Ocean would not be an entirely new endeavor. In 1937, the Kaihomaru, Japanese agribusiness ministry’s fisheries investigation ship led by Capt. Eiichi Taketomi, reached the mouth of the Kolyma River in Siberia via the East Siberian Sea, according to Shuhei Takahashi of Okhotsk Sea Ice Museum, who is knowledgeable about the topic. The ship then set out for a cross-Atlantic voyage with a year-supply of food on it in 1941 before turning around halfway through the journey. The ministry even contemplated a round-the-world trip for the ship from the Arctic to the Antarctic via the Atlantic Ocean until the world conflicts that led to the German invasion of Russia later that year interrupted the plan.

The Kaihomaru’s crew for its fifth voyage included two Meteorological Observatory staff members. One of them was Takahashi's father. Shogo Takahashi, who later served as the director of the Abashiri Local Meteorological Observatory. The daily record of the voyage that Takahashi and fellow observatory staff member kept aboard the Kaihomaru became known as the “Shirokuma (white bear) Diary.”

Urgent Call for Scientists

Nearly 80 years after the Kaihomaru’s tours, the Arctic remains a source of wonder for scientists. Understanding what is happening at the northern end of Earth seems more critical today than ever, as urgent efforts to guard against the negative consequences of global warming continue around the world.

We believe it requires us to pull together all available resources at our disposal to tackle the threats facing the planet and its inhabitants. As Japanese researchers work together to do their part as Team Japan, we plan to share some of our key findings in this Science Report series.

Interviewer: Rue Ikeya

Photographs: Yuji Iijima unless noted otherwise

Released on: May 10, 2017 (The Japanese version released on Dec. 12. 2016)