Data Science – the Humanities' New Tool

History teaches us something new whenever we revisit it, but researchers are finding out that we can learn so much more from our past by bringing data science into historical studies. From projects that combine genomics and archeology to digitization of cultural heritage, a wide range of experiments that merge the humanities and computer science are bearing fruit, shedding light on previously unknown facts. This is allowing researchers to dig deeper into their subject matter to shed light on previously hidden facts – so much so that historians, for example, are now able to add new pages to history books or even rewrite parts of them. Two data science experts involved in this growing research approach explain how this is helping us develop new bodies of knowledge and where it’s all headed.

Ask the Experts: Prof. Naruya Saitou (National Institute of Genetics)

Prof. Saitou serves as professor of genetics for the Graduate School of Advanced Studies and as professor of biology at the University of Tokyo. He has extensive experience in research on species-specific evolutionarily conserved characteristics based on large-scale genomic data comparisons. His 1987 paper with Dr. Masatoshi Nei, his Ph.D. supervisor, which proposed the “neighbor-joining method” for reconstructing phylogenetic trees through the use of evolutionary distance data, has thus far been cited more than 53,000 times. He is the author of “Introduction to Evolutionary Genomics, Second Edition (2018, Springer)”, and many other books.

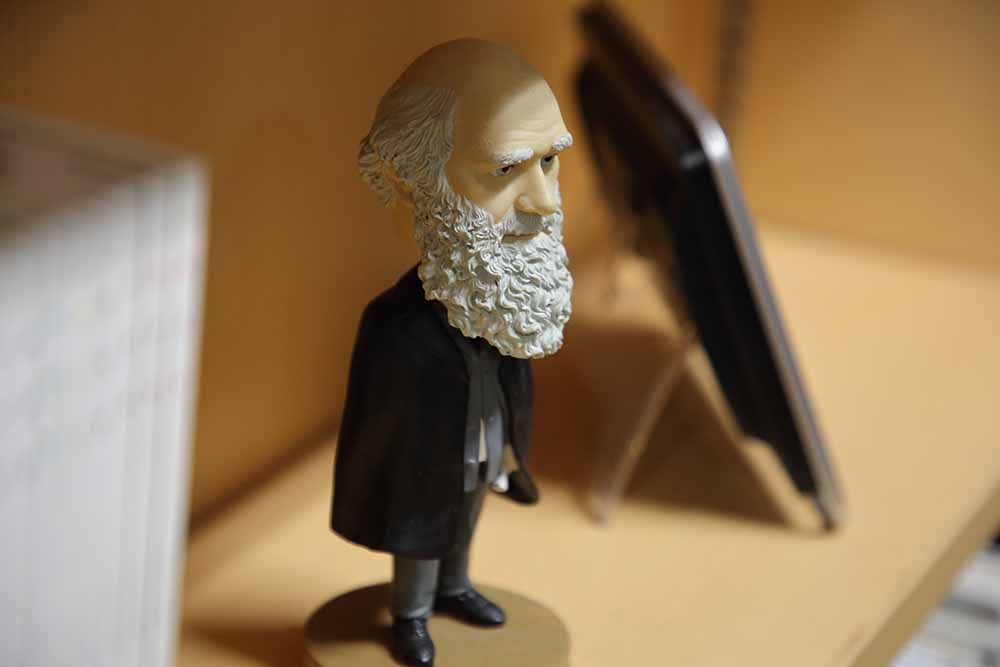

Ask the Experts: Prof. Asanobu Kitamoto (Research Organization of Information and Systems)

Prof. Kitamoto, the director of the Center for Open Data in Humanities at the Research Organization of Information and Systems, serves as associate professor for the Digital Content and Media Sciences division of the National Institute of Informatics and as associate professor of informatics at the Graduate School of Advanced Studies. He has a bachelor’s and doctoral degrees in engineering from the University of Tokyo. His research work centers around image data analysis and application of data-driven science in various disciplines from the humanities to earth science to disaster reduction. His project was among Jury’s Selections at the 2007 Japan Media Art Festival organized by the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the Information Processing Society of Japan’s Yamashita SIG Research Award. Prof. Kitamoto is interested in transdisciplinary research that helps promote open science.

Upside of Drilling into Ancient Artifacts

When and how did the ancestors of the modern Japanese arrive the archipelago from the Asian continent?

It’s a question that fascinates the people of this island country in Far East. A piece of enlightenment came in 2016 when Prof. Naruya Saitou of the National Institute of Genetics (NIG) and his research team analyzed the genome of human bones that had been excavated from the Sangaji shell mound in Fukushima, Japan, and found that the Jomon people – who lived in the Japanese Archipelago between 14,000 and 900 BC– were genetically very different from Chinese and Southeast Asians. The team made the discovery upon visiting the University of Tokyo Museum where the bones were stored and drilling a hole into a back tooth of both a male and female skull to take samples.

Then in 2017, the team concluded that their Japanese ancestors from the continent arrived in three separate time frames instead of two, which had been the popular belief.

“As we compared the genome sequences of people who live in various locations of the Japanese Archipelago (Yaponesia), we found small differences among them. When we looked at where these groups were located, we saw a geographical pattern. And that looked different from the pattern of the Jomon population distribution expected under the two-step migration model,” Prof. Saitou said. “As you can see, humanities information is critical to advancing the research on human evolution. We have countless pieces of archeological artifacts painstakingly unearthed from across the country over many, many decades. Our job is to mine these materials for data. In other words, museums are our ‘field’ of research,” Prof. Saitou said.

He pointed out that such “genomic excavation” is happening more and more across Japan.

“Genomics is finally catching up to the humanities. As we continue with the large-scale genomic project that studies the Jomon people as well as modern-day Japanese from many different areas of the country, we will be able to gain more insights into the evolutionarily conserved history,” he said.

Data at the Crossroad of the Humanities and Science

Bringing together the humanities and data science – the two seemingly opposite ends of the academic spectrum – for the advancement of both is an emerging trend. But, Prof. Saitou said a 19th Century scientist’s concept of how the universe works to is the most useful for explaining why the new approach makes perfect sense. What Prof. Saitou is referring is a Venn diagram that Japanese natural historian and folklorist, Kumagusu Minakata, drew in his letter to a priest. One of the two circles in Minakata’s diagram contains a character that signifies “the mind,” with “matter” encircled in the other. The overlapped area represents “things.”

“There is the human mind, or the subjective world, on one side and physical matters and phenomena, or the objective world on the other. Both have ‘things’ in common, and that’s what we obtain through excavation, such as historical data and archives,” Prof. Saitou said.

“People talk about how far biology has come, but there is so much more that we don’t know,” said Prof. Saitou, who works to advance “evolutionary genomics,” a field that studies how the genome has changed over the course of evolution.

“An interesting thing about genomics is that the ‘matter’ and ‘things’ mirror each other. While adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T) are genetic information, or ‘thing,’ each of them also corresponds to a physical, objective ‘matter.’ This closeness between matter and things is a wonderful thing,” Prof. Saitou said.

“Our goal is to find out how a natural phenomenon called evolution transpired over time by first looking at the genomic changes. It’s important for us to use data as the language to describe what happened in the world that surrounds the human and how it changed. This enables us to prove or disprove history, and I believe that’s what data science is all about,” he said.

Why Data Speaks Against Darwinism

In the research field of biological revolution, Prof. Saitou said, tracking changes in genomic data has already allowed scientists to disprove one of the most widely held ideas: the Darwin theory.

Charles Darwin believed that every species’ survival is dictated by its ability to adapt to the environment through genetic mutations. In other words, genes are continually replaced by those that can better handle environmental challenges, allowing species to produce more offspring and carry forward the mutations. Prof. Saitou calls this theory of natural selection an “illusion,” however.

“The idea that all biological organisms are adjusted to the environment is a fantasy. If better genes outlive worse ones, then no species should die off. But in reality, we see species go extinct all the time. Just this fact itself disproves the natural selection process,” Prof. Saitou said.

He said a close look at genomic data further provides evidence that the theory of natural selection isn’t factual.

“Even when mutations occur in a species’ DNA to better handle the environment, the effects eventually wear off, and those mutated genes will play no more or less part than other genes in the species’ survival. In the end, maintaining the status quo is all that the genes do. We call it ‘purifying selection’ as opposed to ‘natural selection,’” Prof. Saitou said.

In 1968, Japanese biologist Motoo Kimura proposed the “neutral theory of molecular evolution,” stating that the reproductive rates of organisms remain unchanged, or “neutral,” even if nucleotide sequences become altered as the result of mutations. This remains the most trusted theory in the field of evolution studies, Prof. Saitou said.

“Today, we know most genes have gradually evolved from the originals as such neutral mutations repeatedly occurred over long periods of time,” Prof. Saitou said.

Data for Reconstructing the Edo Period

On another front of transdisciplinary data science is the academic community’s effort to pull together all types of historical archives to build big data and analyze it to connect all the dots. The Center for Open Data in the Humanities (CODH) at the Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS) supports this movement by offering datasets, software and other tools to innovate humanities research. In CODH’s March 2018 seminar, “Historical Big Data - Challenges in Transforming Historical Documents to Structured Data for the Integrated Analysis of Records in the Past -,” for example, participants from various disciplines learned how to integrate and analyze seismologic, climatologic and astronomical data obtained from historical records.

“People didn’t have Twitter in old days. Instead of posting on social media, they wrote down in their documents and diaries what they saw and heard. Historical manuscripts and old records are a treasure trove of such everyday information from the past,” said CODH Director Asanobu Kitamoto, who also serves as associate professor for the Digital Content and Media Sciences division of the National Institute of Informatics and as associate professor of informatics at the Graduate School of Advanced Studies.

“For example, we can find weather information in a 300-year-old diary that a family in the western part of Tokyo has kept. In Nagano, people have maintained official records of “Omiwatari” for the past 600 years, which is a religious celebration of the appearance of an ice ridge formed along a crack on a frozen Suwa Lake. Shrines in Kyoto have also long recorded the day cherry flowers blossomed every spring,” Prof. Kitamoto said.

He said records from the Edo period are particularly abundant, which is the reason he is focusing his research on that period. Researchers can use such records to reconstruct past climate conditions, put together historical disaster information and even analyze correlations between natural events and social, political or economic events, including market fluctuations in the modern era, and groundwater management. The CODH works to foster the research community of digital humanities by supplying its technological expertise and research gathering.

“Reconstruction of history through comprehensive analysis of historical records has been a growing movement worldwide. The Venice Time Machine, a project to create digital archives of records covering Venice’s 1000-year history to reconstruct the city from the ancient days, is an example,” Prof. Kitamoto said. “But research teams engaged in these digital humanities projects are scattered across the globe. We are hoping to establish a system for bringing together the research results, digitizing them and making them accessible to all researchers,” Prof. Kitamoto said.

Open Science Through Standardization for Visual Art Curation

The CODH is also an active participant in the International Image Interoperability Framework, or IIIF, which is an international initiative to develop standard technology and systems for image delivery. IIIF aims to make digital images – those that belong to museums, libraries and other institutions and individuals from around the world – accessible to researchers and the general public everywhere. The National Diet Library of Japan, the British Library, the National Library of France and “Europeana,” an online repository of digitized items, as well as Oxford University and other universities, use IIIF to provide access to more than 350 million digital images. As part of its effort to help build a IIIF community in Japan, the CODH has developed an application called “IIIF Curation Viewer,” which allows users to view the National Institute of Japanese Literature’s old books on the CODH’s website.

“IIIF Curation Viewer lets you cut out the parts of images that interest you, such as people’s faces, and curate them just like making a scrapbook. To do something like this, we used to visit museums, take photos of the images or photocopy them and cut and paste the parts we want with scissors and glue. Now that we have this Viewer, we can do the same thing hundreds or thousands of times faster,” Prof. Kitamoto said.

As curation and analysis of images becomes easier, researchers are tapping more into visual resources to make discoveries.

“We curated just facial images from our collection as an experiment. Comparison of these images revealed that a face appears in one book is painted very similarly to another face that appears in a different book. Picture books from the Edo period are comprised of paintings and calligraphy, and we know people used to ask art studios that specialize in either painting or calligraphy to get each part done separately. It is possible that there were templates that art studios were using to paint faces – which would be somewhat similar to the method that today’s manga artists use,” Prof. Kitamoto said.

He noted that everyone in the research community significantly benefits from open access to research data, as it allows them to review each other’s results and share their interpretations. To make this possible, data needs to be aggregated first, and a part of the research workflow standardized.

“Data science can contribute to digital humanities, but that’s not enough. Accelerating innovation in digital humanities through data science is our mission,” Prof. Kitamoto said. He wants to provide scholars’ a tool to share with others the knowledge and materials that are locked in their brains. “Anyone can curate images that they find on any IIIF-enabled websites – that’s my vision for the participatory citizen science that we are trying to promote,” Prof. Kitamoto said.

Discoveries at the Crossroad of the Humanities and Computer Science

One of the COHD’s curation series that has drawn the most public participation is the Dataset of Edo Cooking Recipes. The COHD launched the series in 2017 with a collection of egg recipes from a cookbook “Manbo Ryori Himitsubako” published in 1795. The egg recipes have even made their way onto a popular online recipe service, Cookpad, to reach the general public across Japan.

This experience was a lesson to learn that, just make data accessible is not enough to make the full use of it, according to Prof. Kitamoto.

“What’s interesting about humanities data is that we can study connection to the history and culture behind the data. I hope to use humanities data to not only advance computer science but also gain new understanding in the humanities,” Prof. Kitamoto said. “Computer scientists need to go beyond the research practice of putting someone’s data into a black box and get the result. When the same cutting-edge analysis tools become accessible to non-computer scientists, our field cannot grow further. We have to think about better ways to access new data, what kind of new knowledge we could gain from data, and those sorts of things. In other words, I believe that the future of our field depends on how we try to effectively and creatively handle data,” Prof. Kitamoto said.

Interviewer: Rue Ikeya

Photographs: Yuji Iijima unless noted otherwise

Released on: September 26, 2018 (The Japanese version released on February 10, 2018)